FINALIST

2017 AMERICAN PRIZE

“SPECIAL JUDGES CITATION”

“The place was electric!”

“Audience members were on their feet!”

The rich heritage of the African-American Spiritual

18 minutes

SATB and Baritone soloist

Scroll down for recordings and program notes

Reduced orchestration for 11 players available. See below.

FULL ORCHESTRATION

2(1.2/pic), 3(1.2.Eh), 2cl, 2bsn – 4hn, 2tp, 3tbn, 1tba – tmp+1 – str

CHORAL SCORES

THE ELATION OF LIBERATION

“There’s A Stirrin’ In The Water” celebrates the bonding of all Americans to become one indivisible nation and stand tall alongside each other. [It] brings forward a compendium of well-known spirituals which, through their transfiguration, brings the performers and audience into a journey that leads the soul from the shadows of bondage to the elation of liberation. —Kevin Scott, Conductor , Springfield Symphony Juneteenth concert

Excerpt, Akron Symphony premiere

Complete work, reduced orchestration

Performed by the Gary United Methodist / First Presbyterian of Wheaton Festival Chorus and Orchestra, Jennifer Whiting, conductor

Video -piece starts at 31:05

Conductor Christopher Wilkins comments on the 2016 premiere There’s a Stirrin’ in the Water

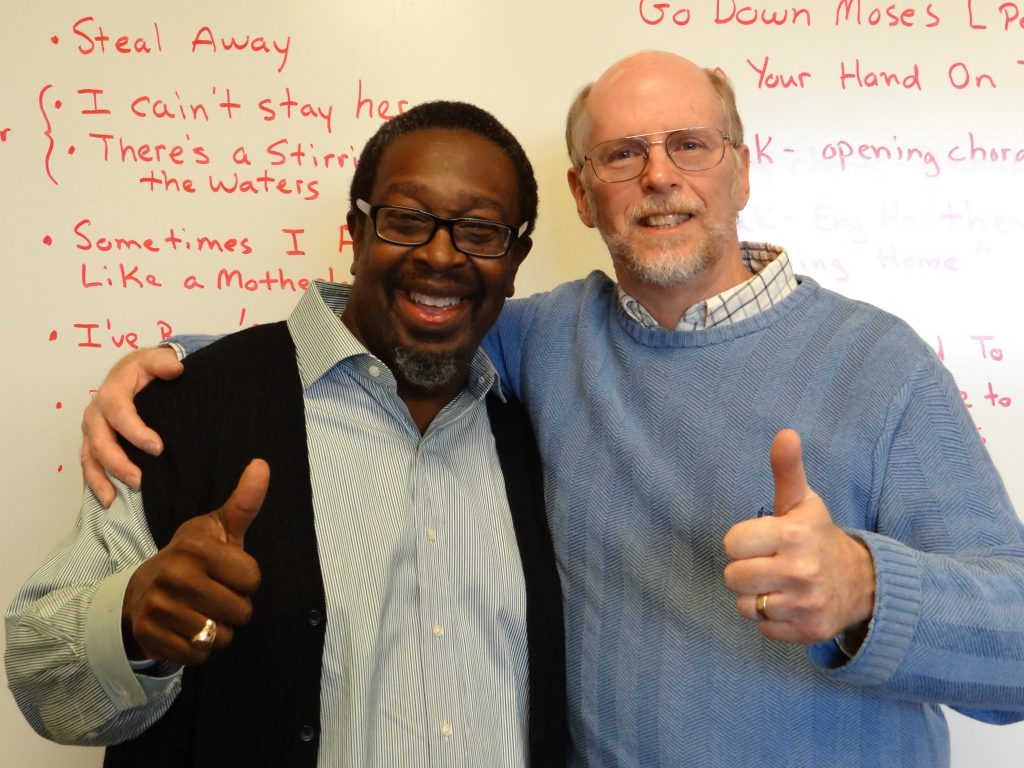

Podcast: Interview with Composers Charles Myricks, Jr., and Jesse Ayers about There’s a Stirrin’ in the Water

Performances

- 2025, Springfield (Massachusetts) Symphony Orchestra and Springfield Extended Family Choir, Kevin Scott, conductor

- 2024, Gary United Methodist / First Presbyterian of Wheaton Festival Chorus and Orchestra, Jennifer Whiting, conductor. (Two performances, two venues)

- 2019, Chicago Bar Association Symphony Orchestra and Chorus, David Katz, conducting.

- 2018, The Fountain Inn Symphony (South Carolina), Michael Moore, conducting.

- 2017, The Fort Bend Symphony Orchestra & Chorus (Texas), Dominique Røyem, conducting.

- 2016, The Akron Symphony Orchestra & Chorus, Christopher Wilkins, conducting.

Spirituals included in this work

- Steal Away (vocal solo followed by chorus)

- Sometimes I Feel Like A Motherless Child

- Deep River (vocal solo)

- God’s Gonna Set This World On Fire

- I am Determined to Walk With Jesus (features alto section)

- Ain’t Got Time To Die (soloist & chorus, call & response)

- Various other instrumental quotes from spirituals used as transition material

Program Notes

African-American spirituals constitute one of the largest and most significant repertoires of American folk music. Birthed in slavery, the Spirituals were a means of solace and encouragement, combining Biblical promises with expressions of the hardships of slavery.

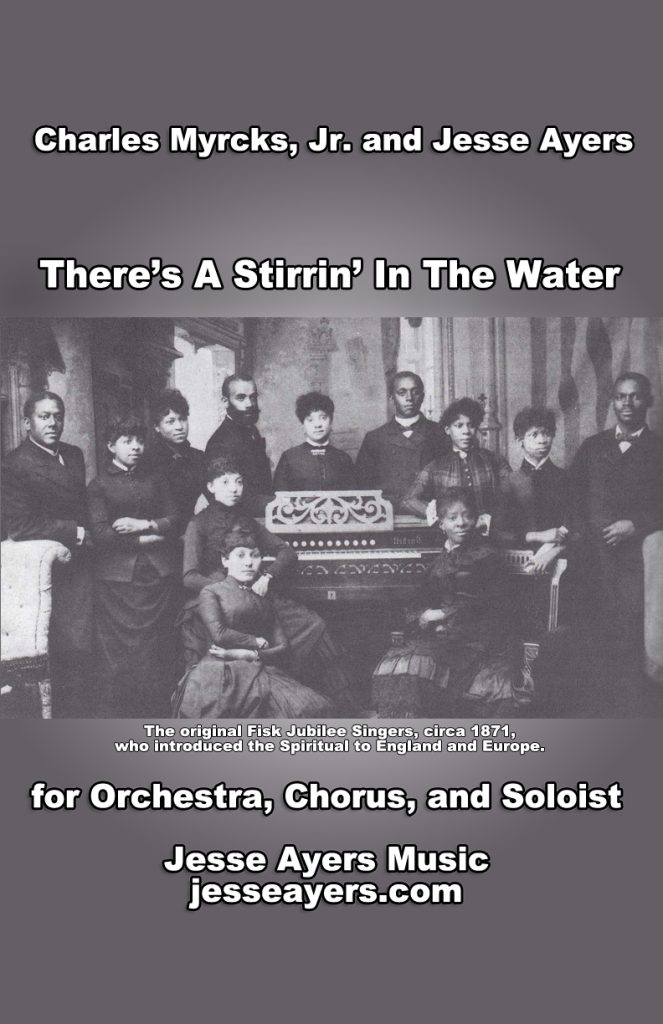

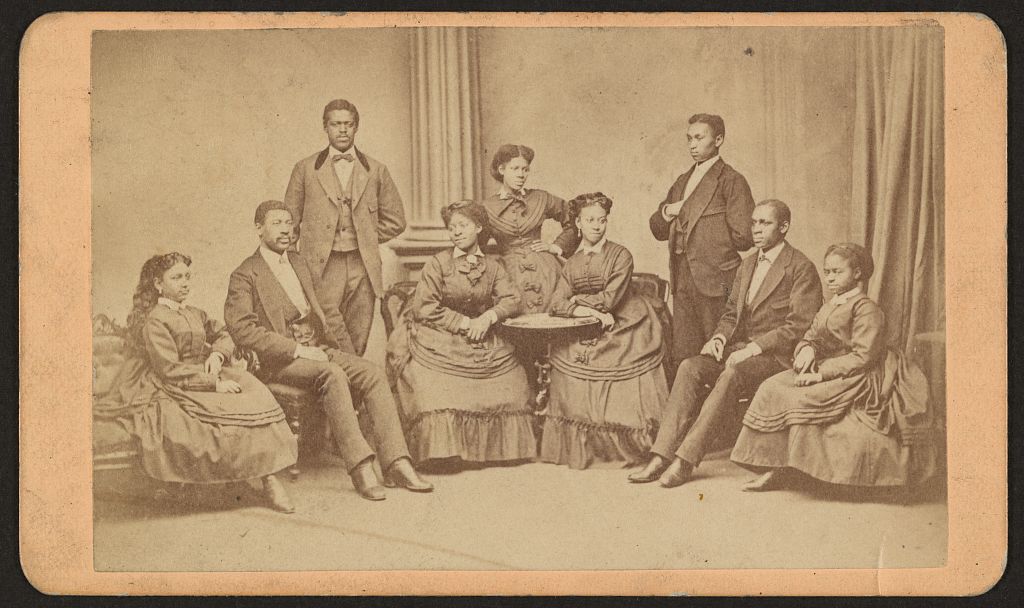

During the first few years of the 1870s, this literature became known to the world through the agency of a newly formed nine-voice vocal ensemble at the recently incorporated Fisk University in Nashville, founded to educate recently freed slaves. This group, formed to help raise awareness of the new school and to aid fundraising efforts, adopted the name The Fisk Jubilee Singers. Although the Singers first tour, lasting several months, was fraught with hardship, illness, and hunger, by the second year they were performing at the White House for President Grant and were touring England and Europe, singing before crowned heads of state, including Queen Victoria. The talent of the singers, and the power of this music, heretofore unknown to the world at large, propelled these young men and women, most of whom were slaves just five years prior, onto the world stage and dining as guests of honor with the royalty of Europe.

There’s A Stirrin’ In The Water was birthed over a dinner meeting between Christopher Wilkins, conductor of the Akron Symphony Orchestra, Charles Myricks, Jr., a composer, pastor, and former executive at Word Records, and Jesse Ayers, an orchestral composer and university music professor, during which Wilkins proposed that Myricks and Ayers collaborate to create a work celebrating the Spiritual. Both Myricks and Ayers took to the idea, as well as to each other, right away.

Myricks writes, “I sought to renew our acquaintance with several well-known traditional Spirituals, presenting them in a way that highlights their power for confronting incredible hardship with divine defiance. The Spirituals always reflected, renewed, and revealed a source of the strength of the slaves, their belief in a just, all-knowing, almighty, and loving God, who is willing and able to set captives free.”

Ayers adds, “Chuck and I agreed from the outset that this piece needed to be more than an “arrangement” for chorus with orchestral accompaniment. We wanted an integrated symphonic fabric of equally important players—the orchestra, the chorus, and the soloist—with no one element being any more or less important than the others. We worked to include the range of emotions found in the spirituals, from the songs of sorrow (“Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child”), to the songs of sustaining faith (“Steal Away” and “Deep River”), to the songs of victory and praise (“God’s Gonna Set This World” and “Ain’t Got Time to Die”), with Chuck shaping the order of songs to form the work’s arch.

In addition to the songs presented by the chorus, the attentive listener will hear instrumental quotes of several other spirituals in the orchestral interludes, including “Go Down Moses,” “Keep Your Hand On The Plow,” and “Give Me Jesus.”

Near the end of the work, as the chorus repeatedly sings the text “Glory and Honor,” the listener will hear several glissandi from the horn section, imitative of a shofar. These glissandi are a direct reference to the silver plated ram’s horn trumpets described in Leviticus 25, to be sounded once every 50 years to proclaim the Year of Jubilee, a year in which all debt was canceled and all indentured servants were set free. This musical proclamation of freedom here derives from from two brief passages from Scripture: “God inhabits the praises of his people” (Psalm 22:3) and “where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is freedom” (2 Corinthians 3:17). The chorus is singing “glory and honor,” God inhabits those praises, which means His Spirit is present, which brings freedom; so the Jubilee shofars proclaim this freedom over the audience.

The work also has several quotes from Dvorak’s Symphony No. 9 “From the New World,” some obvious, some less so. Dvorak was heavily influenced by a young African American student he heard singing the halls at the National Conservatory in New York City, where Dvorak was the director. That student was H.T. (Harry) Burleigh, who went on to become one of the foremost arrangers of spirituals. It seemed fitting to the composers of the present work to “complete the circle” by including quotes in the fabric of their work that are drawn from phrases and harmonic progressions found in Dvorak’s “New World,” which itself was heavily influenced by the spiritual through Dvorak’s contact with Burleigh.

—J.A.